The Council was a communist front group that believed that the USSR and the United States should join together in their common fight against fascism in the 1940s. We all know how that worked out. In 1946, the House Un-American Activities Committee investigated it and in 1947 the Council was indicted. It finally closed in 1991 just as the USSR itself was sliding into the dustbin of history. Of course, the Stalinist mindset is now the required worldview on U.S. college campuses and elsewhere. Perhaps that’s what Nikita Khrushchev had in mind when he said “We will bury you,” Мы вас похороним! These days, he might say, "We will give you the ideological tools and strategies so you can bury yourselves." So the flavor of the worst of the USSR is digging in to the current frenzy to unmask spies and wreckers who deviate from the ever-shifting Twitter/media party line. But that's another discussion.

Anyway, the council helped me realize a long-term dream—to study Russian. I had always been curious about the USSR. I almost took Russian at Princeton, which had a great program, but I got cold feet and took Spanish. My curiosity intensified after I read all three volumes of The Gulag Archipelago in 1983. I finally got a Barnes & Noble book on Russian and I earnestly read it for years on the subways. But I always noticed the council’s classified ads on the back page of the Village Voice offering Russian classes. This tempted me, but the name of the group told me it was a front for the Reds. I didn’t want to get on any FBI watch list because of language study. My daring act was buying The English-language Moscow News at a newsstand on West 42nd Street.

|

| My subway reading companion |

But starting in 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev brought more openness to the USSR, with glasnost and perestroika. The USSR was changing, so I threw caution to the wind and signed up for a beginners class, given at the Ukrainskaya Dom, or Ukrainian House, in the East Village. The teacher was the wife of a Soviet official at the UN.

The challenges were immediate. Russian written in the Cyrillic alphabet, akin to Greek, so I had to learn a lot of new letters. While Russian has some cognates with English, it’s nothing like German or Spanish. And the case structure! I still remember the declensions in this order: nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, instrumental and prepositional. Perfective verbs, imperfective verbs, soft sounds, hard sounds, words with 30 letters. Pronunciation could be tough. Once I mispronounced the phrase for “crime and punishment," преступление и наказание. The teacher laughed merrily and revealed I had actually said, “Crime and execution!” That must be s a real knee-slapper in Russian.

But I learned something. I wanted to, because I went on a tour of the USSR in September 1987, the high tide of glasnost. I could at least read the street signs. I came back with lots of constructivist-style posters, an art form I greatly admire.

I went on to study Russian at NYU’s school of continuing education. Since then I’ve moved on to other languages. But Russian studies paid dividends. I still have my language books, including this dictionary I got before my 1987 trip—I can pick up on words in Ukrainian, Polish, Czech and Serbo-Croatian based on their connection to Russian. I buy CDs in Russian at Goodwill when I see something that interests me, like the greatest hits of Anna Pugacheva. And when I get bored, I doodle in my loopy cyrillic script. Often I’ll write “ya nhe znayu,” я не знаю, which means I don’t know, or ”ya govaryu na-russkom,” я говорю на русском I speak Russian. If you're a James Bond fan, you'll recognize my scribbling of the phrase and organization called SMERSH from Смерть шпионам (SMERt' SHpionam, "Death to Spies.)" I’ve used simple phrases to banter with Russian barbers in New York and Katonah. They get a kick out of this.

I've also seen how learning some Russian, or any other language, can very quickly connect me with other people. It may be for only a few minutes, but acknowledging somebody in their native language can dent the isolation felt by people outside the dominant language culture. This happened when I visited Israel in 2017; many Russian-speaking immigrants work in jobs such as running the checkrooms of museums. At the Bauhaus Foundation in Tel Aviv, the woman who took my backpack appeared to be Russian, so I simply thanked her and said one or two other things I could manage. She was a human with her own language, perhaps she rarely felt recognized as such. She responded positively. I felt like we connected and that felt good.

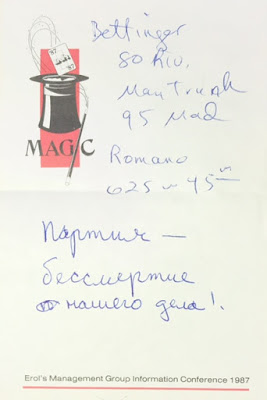

|

| Doodles in Russian, meaning something like "The Party is our eternal work!" |

So many thanks, National Council of American-Soviet Friendship. Am I on a list in your archives at NYU? I really should check that out. In the meantime,большое спасибо товарищ wherever you are.